Working conditions and environmental situation on pineapple plantations in northern Costa Rica

By Marylaura Acuña Alvarado and Mauricio Álvarez from the Socio-Environmental Kiosk Programme, University of Costa Rica

(Reproduced from https://surcosdigital.com/situacion-laboral-y-ambiental-de-la-pineras-en-la-zona-norte/)

Participants in the Socio-Environmental Kiosk Programme have been working in various communities of northern Costa Rica. By means of social action and investigation they have been looking into the world of paid work on pineapple plantations. Work has been carried out with community and union organisations, such as the Private Sector Workers’ Union (SITRASEP) in Santa Fe de los Chiles. Throughout 2018, this branch of the union constantly denounced working conditions and eventually went on strike, causing financial losses for the company Exportaciones Norteñas. Although the agreements reached as a result of the strike were favourable for the union (it demanded that basic standards be respected), so far the company has not kept its word.

This strike set an important precedent: already this year three more strikes have broken out on other plantations in the northern region. Men and women workers of the companies Bella Vista S.A. and B & Jiménez S.A, in Los Chiles canton, and Valle del Tarso S.A in Upala canton have walked out in protest. The Bella Vista branch of SITRASEP continue striking not only in response to precarious work conditions, but also as a protest against the persecution union members have been subjected to; some of whom have been unfairly dismissed and have not received their end of year bonus for last year. The other two strikes ended with satisfactory agreements for the men and women workers. (Socialismo Hoy, 2019).

The union organisations seek to expose and challenge the hidden realities of agroindustry, where men and women workers are marginalised and therefore vulnerable. Their marginal status means they are practically invisible as part of the social structure and excluded from discourse on development. The majority of workers in the Costa Rican pineapple industry are poor migrants and they generally have a darker complexion. Although the exploitation they are subjected to is their only means of survival, they are capable of standing up against injustice.

Between 1991 and 2014 pineapple production increased by 91%, with yields going from 29 metric tonnes per hectare to 56 (Rodríguez, 2015). This increase isn’t necessarily due to technological improvements (such as mechanisation or automation of production, as has been seen in other sectors of the economy); it may be a result of an improvement in supplies, such as seeds, fertilizers and herbicides. In the case of the large companies of the northern region, it also has to do with an increase in the intensity of manual labour, which continues to be of central importance. Shifts have been extended, although the number of workers taken on has not gone up. Most workers are paid piecework and work is divided in order to maximise productivity. For example, the “parcelero” is responsible for eliminating all the weeds on a 15 to 20 hectares plot – basically making sure that nothing but pineapples grow there. He must also keep paths clear and make drains. Shifts may be as long as 12 hours a day and are paid by the hour.

Regarding contractual arrangements, companies generally subcontract various functions to anonymous groups as a way of getting around employer–employee responsibilities. This practice has enabled companies to take advantage of migratory workers who don’t have official papers or visas. The secretive and irregular situation of workers has created the perfect backdrop for the illegal trafficking of drugs and people, although this issue is well hidden and has not been explored in depth.

A report presented to the University Council of the UCR concerning offences detected during visits by the Ministry of Labour to pineapple plantations found high levels of infractions regarding: personal protection (protective clothing and adequate provisions), legal requirements regarding access to toilets, overtime payments, sexual harassment, minimum wage and other issues. (Special commission regarding the socio-environmental consequences if pineapple production, 2018).

The persecution and undermining of unions, the intimidation of union leaders and the use of black lists are common practices among companies in response to organisations which speak out against unfair working conditions. It also demonstrates how this sector is highly on a workforce that is structurally flexible and vulnerable for the continuing growth of production.

The location of pineapple plantations in areas where many families live by subsistence farming and common goods are shared amongst communities is no coincidence. Subsistence farming and the domestic work done by women cannot be measured in economic terms, yet this work provides support for plantation workers and makes it possible for companies to pay low salaries which wouldn’t otherwise be enough to ensure the survival of families and the continued supply of cheap labour.

Looking at the relationship between capital and labour in the pineapple industry we see that growth in this sector has been possible not only thanks to state-generated improvements in production and exportation (probably the most important factor being the government’s selective enforcement of regulations), but is also a result of the industry’s reliance on the subordination and exploitation of the vulnerable rural population, above all women and migrants.

Context

The cultivation of non-traditional crops for export was promoted in Costa Rica by state bodies through political and economic incentives. This has had a negative impact on the production of subsistence crops for domestic consumption. The hasty and unregulated growth of pineapple plantations is maintained through practices of land-grabbing, forest devastation, the invasion of protected areas, water contamination, community displacement, destruction of roads and labour exploitation.

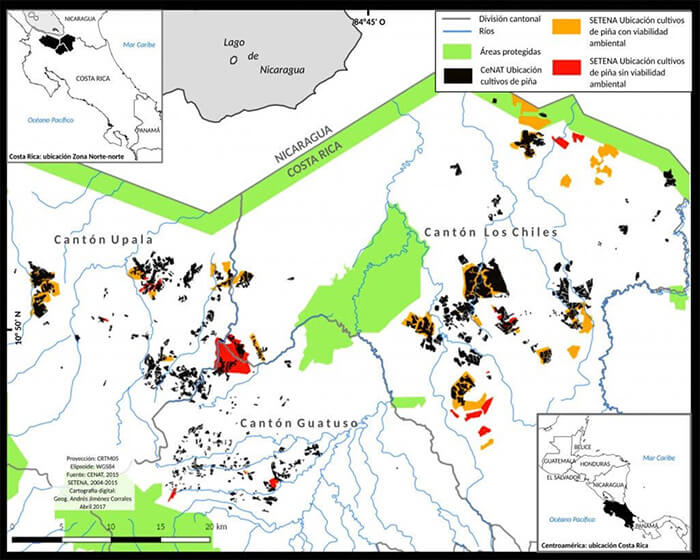

Costa Rica is the largest producer and exporter of pineapples in the world, and this title has come at a price. The growth of the industry has been so fast that in 2014 revenue from pineapple exports almost equalled those of banana and coffee. Furthermore, the number of pineapple producing companies continues to increase, as does the number of countries buying Costa Rican pineapples. The number of hectares of pineapple plantations increased fivefold between 2000 and 2016, from 11 000 to 58 000 hectares (Obando, 2017). In 2017 it may have reached more than 66 000 hectares, according to satellite images from the the PRIAS Laboratory of the National Centre for High Technology (CENAT) of the National Council of University Rectors (CONARE). (http://www.snitcr.go.cr/) Pineapple production is mainly in the hands of a few large companies and plantations are in the northern, southern pacific, and northern Caribbean regions.

Since 2009, the Socio-Environmental Kiosk Programme has been working on behalf of the University of Costa Rica Community Organisation in the northern region. A research article produced by the programme and published by the State of the Nation Report shows the socio-environmental impacts of the uncontrolled growth of the industry. In this region plantations expanded more than 23 times over between 2004 and 2015. This was apparently due to just seven projects which applied for environmental viability from the National Technical Environmental Secretariat (SETENA) for the cultivation of 4.175 hectares.

Analysis of documents compiled by SETENA concerning agriculture in the region (Upala, Los Chiles and Guatuso cantons) concluded that: “firstly, some of the pineapple producing companies do not have environmental viability licences; secondly, SETENA lacks the resources to continue, in the medium and long term future, to monitor the projects which do have authorisation; and thirdly, the data compiled in the documents does not enable an analysis of the impacts of the crops on the land and biodiversity.”

Between 2004 and 2015 the environmental impact of 47 projects in the northern part of the northern region were evaluated. Of which, more than half (29) were from Los Chiles canton. The evaluations indicate that: 65.9% of the projects were granted environmental viability, 21.3% were refused, 10.6% are still being studied and for 2.1% no information was registered.

This map contrasts pineapple cultivation data from the National Centre for High Technology (CENAT) with the records from SETENA.

More than half of the pineapple plantations are in the northern region. This is no coincidence: it is due to a series of environmental, social and economic factors which have allowed the large companies to move in. The historically marginal position of the region, its underdevelopment, its under-representation in national institutions (typical of boarder regions), the abundance of cheap unskilled labour and its extensive tracts of agricultural land all contribute to make this the ideal place for the devastating expansion of agroindustry.

Precisely these socio-geographical factors have been used to justify the expansion of monoculture plantations in the hegemonic discussions about the issue. It is claimed that pineapple cultivation would miraculously solve issues such as poverty, unemployment and underdevelopment. This is not a total exaggeration: the advance of agroindustry has resulted in the salaried employment of the rural population. However, the other side of the coin is that the role of rural communities as principle food producers is under threat. This capacity is being stolen from them. The separation of the rural population from their means of livelihood (which are transformed into commodities) goes hand in hand with their introduction to paid agricultural work. The majority of this work is of an exploitative nature and detrimental to family farming and food security.

The data show that while in the year 2000 unpaid family based work was predominant in rural areas, by 2010 the percentages are reversed and 65% of men and women workers are in paid employment (A. G. Rodríguez, 2016). Pineapple production is not the only source of employment in this region: according to the National Statistics and Census Institute (INEC), the service and commercial sectors have also grown rapidly.

The fact is that while representatives of the National Chamber of Pineapple Producers and Exporters (CANAPEP) and high ranking government officials sing the praises of pineapple monoculture, the vast profits made through the exportation of the crop do nothing to improve the lives of the people in the areas where the fruit is produced. The hidden truth is that in this region the expansion of the pineapple industry has devoured at least 3192 hectares of forest (Moccup, 2017). The national wildlife refuge Caño Negro, the northern border refuge corridor, the Maquenque Wildlife Refuge and Barra del Colorado refuge are all disappearing bit by bit along with other important sites. What’s more, this devastating expansion is maintained through the exploitation of a vulnerable workforce.

These issues are widely debated. Ever more frequently and with increasing fervour, community organisations and unions are speaking out against the injustices committed daily in their communities and places of work. In the case of union organisations, they are making ever more demands for fair and dignified working conditions. In the northern zone, SITRASEP stands out. Branches of this union have in recent years concentrated on denouncing and protesting against breaches made companies. For example, the men and women workers of Santa Fe (Exportaciones Norteñas S.A.) and the Union (packaging company Bella Vista S.A.) both of Los Chiles.

The rapid and aggressive expansion of pineapple monocultures has, in most cases, taken place in irregular circumstances and the authorities have at times turned a blind eye. It has been possible through the use of harmful practices which, by their very nature, make the production of this fruit destructive to the environment, and through the exploitation of labour. These conditions, so typical in the production of export crops from Latin America, are precisely what enable a few companies to make huge profits. It is essentially an extractivist model hiding behind a discourse about sustainable development.

References

Araya, J. March 8th 2017 The expansion of pineapple plantations devours 5.568 hectares of forest. Source: >http://semanariouniversidad.ucr.cr/pais/expansion-pinera-se-comio-5-568-…. May 9, 2017.

Special commission concerning the socio-environmental impacts of pineapple production (2018). (Comisión Especial sobre las consecuencias socioambientales de la producción de piña). Final report

National Statistics and Census Institute. (2011). National household survey (Encuesta Nacional de Hogares).

Obando, A. (2017) The truth about pineapples: the socio-environmental conflict behind the pineapple plantations in Upala, Guatuso and Los Chiles cantons (El Estado detrás de la piña: El conflicto socioambiental del monocultivo de piña los cantones de Upala, Guatuso y Los Chiles) (2000-2015) (Bachelor’s degree thesis for political science) University of Costa Rica, office of Rodrigo Facio.

Rodríguez, A. (October 18, 2015) Agricultural yields in Costa Rica increased by 78% in the last two decades. Source: Costa Rican newspaper ‘El Financiero’ https://www.elfinancierocr.com/economia-y-politica/productividad-agricola-de-costa-rica-crecio-78-en-ultimas-dos-decadas/UKDPDVC2LJALPFHG5JRU333WBI/story/

Rodríguez, A. G. (2016). Rural transformation and family agriculture in Latin America: what the household surveys reveal. (Transformaciones rurales y agricultura familiar en América Latina: una mirada a través de las encuestas de hogares) Source: /f0>http://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/40078

Socialismo Hoy (18 de enero de 2019). Piñeras: Three strikes in less than a week in the northern region. Source: (tp://socialismohoy.com/pineras-3-huelgas-menos-semana-zona-norte/)

Valverde, K., Porras, M., & Jiménez, A. (2016). Expansion due to carelessness: Pineapple plantations in Los Chiles, Upala and Guatuso cantons Costa Rica (2004-2015). (La expansión por omisión: Territorios piñeros en los cantones Los Chiles, Upala y Guatuso, Costa Rica).

State of the Nation Programme. (Programa Estado de la Nación). Source: http://estadonacion.or.cr/files/biblioteca_virtual/022/Ambiente/Valverde_Ketal_2016.pdf

English

English Español

Español